My mother may have introduced me to monster stories, but my deep abiding love of horror didn’t come until later, after her death.

I’ve never talked about my childhood much. I have a collection of throwaway lines I can trot out when necessary: “It wasn’t a good time.” “It was a special kind of hell.” “A place I’d prefer not to go back to.” If you seek out my early spoken word/poetry, you’ll get more hints, like in a piece where I address the root of what’s wrong with me as, simply, “I wasn’t hugged enough as a kid.”

There’s truth in all these things, but what’s maybe more honest is: I don’t know how to tell my story. I realize that’s a ridiculous confession for a writer. But it’s true. I was raised to say nothing, protect everyone, and let someone else write my narrative.

You might say my family is a fortress of secrets, some I keep and some I’m still learning of to this day. In recent years, there have been cracks in the foundation and as a journalist I can’t stop scraping at them, wondering what other truths might spill out. I spent my entire childhood wondering why we were the way we were. Little did I know that I’d have to wait until my forties to get any answers.

I say all that because it’s in that question “why?” that my love of horror was born. As a kid, I didn’t really have anyone I could talk to. “Why?” was a question that would routinely be answered with "Because I say so” or “Because that’s just the way it is,” so I learned early to just stop asking. As I got older I figured out there were “safe” things to discuss and others that should be avoided at all costs. Childhood was full of landmines. I mostly learned how to be damned good at being invisible.

But just because I had no one to tell me “why” didn’t mean that I didn’t still want to know the answers. I’ve always been the kind of person who thrives on facts, knowledge, and understanding. As an adult, I would go on to seek understanding through therapy and support groups and lots of non-fiction texts. But as a kid none of those things existed in my decidedly small universe, but the library did (both school and public), and my father didn’t care what I read. So not only did I read to escape, I started to look for myself (and my experiences) in fiction. Of course, I knew that stories weren’t real, but finding a connection through something creative would still be finding a connection. And I can’t tell you how hungry I was for connections back then.

The teen fiction and family sitcoms of the day felt twee and unrelatable to kid me. A family that you could talk through life’s tough shit with and not get grounded for eight million years? What was that? Might as well have thrown a fucking unicorn into the story. In my world, if you screwed up and got into trouble, you figured it out yourself and hoped to hell no one ever found out. (Side note: I now raise my daughter in a household where we talk about anything and everything, so I guess unicorns do exist after all.)

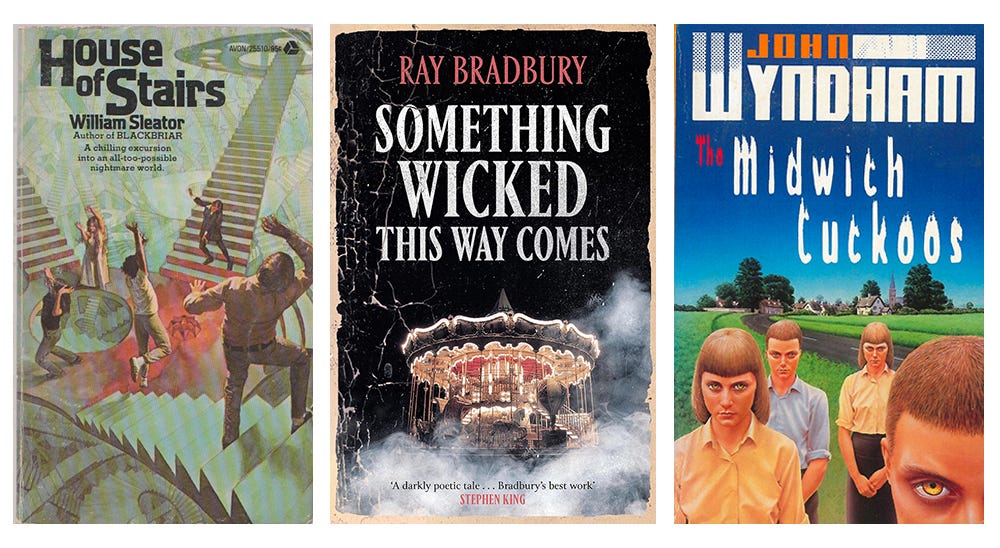

Before I discovered grown-up horror, the stories that left the biggest impression on me included William Sleator’s House of Stairs (1974), Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962), and John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos (1957). Like everyone else my age, I read some Beverly Cleary, Judy Blume, and Sweet Valley High as well, but I never connected with them quite the same way as I did with the dark stuff. The dark stuff made the gears in my brain turn. My childhood was dark, and horror was calling.

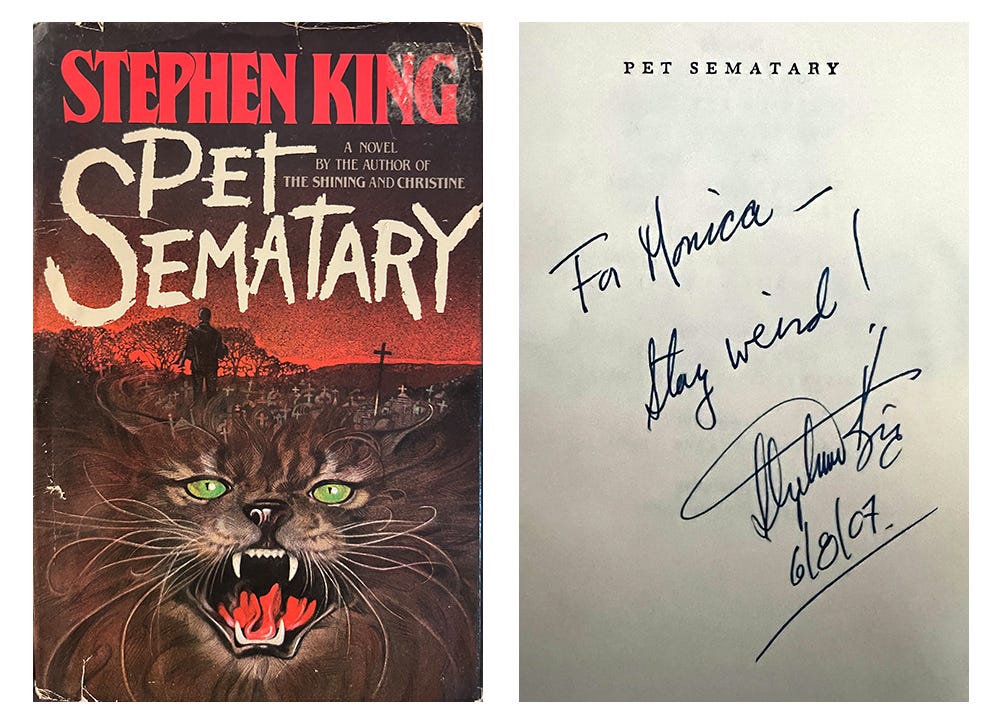

I wish I could remember who was my gateway drug to adult fiction, I think by the time I plucked James Herbert’s The Rats off the supermarket spinner on the way to the cottage when I was, maybe, twelve-ish (note to self: ask Dad when we sold the cottage), I’d already started plowing through Stephen King’s catalogue. I know a first edition of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary is the first hardcover book I ever purchased for my someday “library,” but I don’t know where or when I bought it. (I did get it autographed by King in 2007 backstage at an event here in Toronto, which was a triumphant moment for twelve-year-old me who used to spend recesses on the school playground telling her best friend how she dreamed of growing up and someday - maybe, just maybe - working in entertainment and meeting her heroes). By eighth grade, I’d read the complete back catalogues of both King and Clive Barker and did a big project for English class comparing their then-bodies of work. Looking back, I guess you could say I’ve been doing this Library of the Damned thing since way before it was a glimmer in my eye. Anyways, my gateway drug had to be King (likely discovered on the shelf of my dad’s girlfriend at the time) or Dean Koontz or V.C. Andrews. And no doubt, I was young, definitely too young.

Or maybe not. Sure, the V.C. Andrews books were weird and salacious, but they also featured families way more messed up than mine, which provided an then-unexplainable, previously unexperienced sort of catharsis. If those poor kids could survive all that madness (and maybe escape), surely I could too? Horror had a similar effect. Even if I didn’t see myself or my experiences in most of the stories I devoured, I loved reading about people going through much tougher stuff than me (no matter how wild and unrealistic) and standing up and fighting back and overcoming. As a kid, I was a sucker for a happy ending.

Life was dark back then and in dark stories I found comfort.

I eventually grew up and moved out and started therapy/healing. I distanced myself from the problem people, and as the decades passed I learned about trauma, intergenerational trauma, and CPTSD. My relationship with horror changed accordingly, but never waivered. I still love to lose myself in a book, but I no longer read to escape the world. (Life is good; I got my happy ending.) Nowadays, if a story swallows me whole, it’s because it’s a damn good story.

That said, I’m absolutely enamoured with the way that contemporary horror grapples with mental health and toxic family systems. A lot of it strikes me as just the sort of stuff that young me was seeking all those years ago, but of course that was the ‘80s, and the world still needed time to catch up and learn how to talk about the hard stuff. I’m happy to be here now that it did.

My friend, we have much in common. Did you read the description of my substack, by the way?